The Brahmaputra’s Mighty Roar

The Brahmaputra’s Mighty Roar

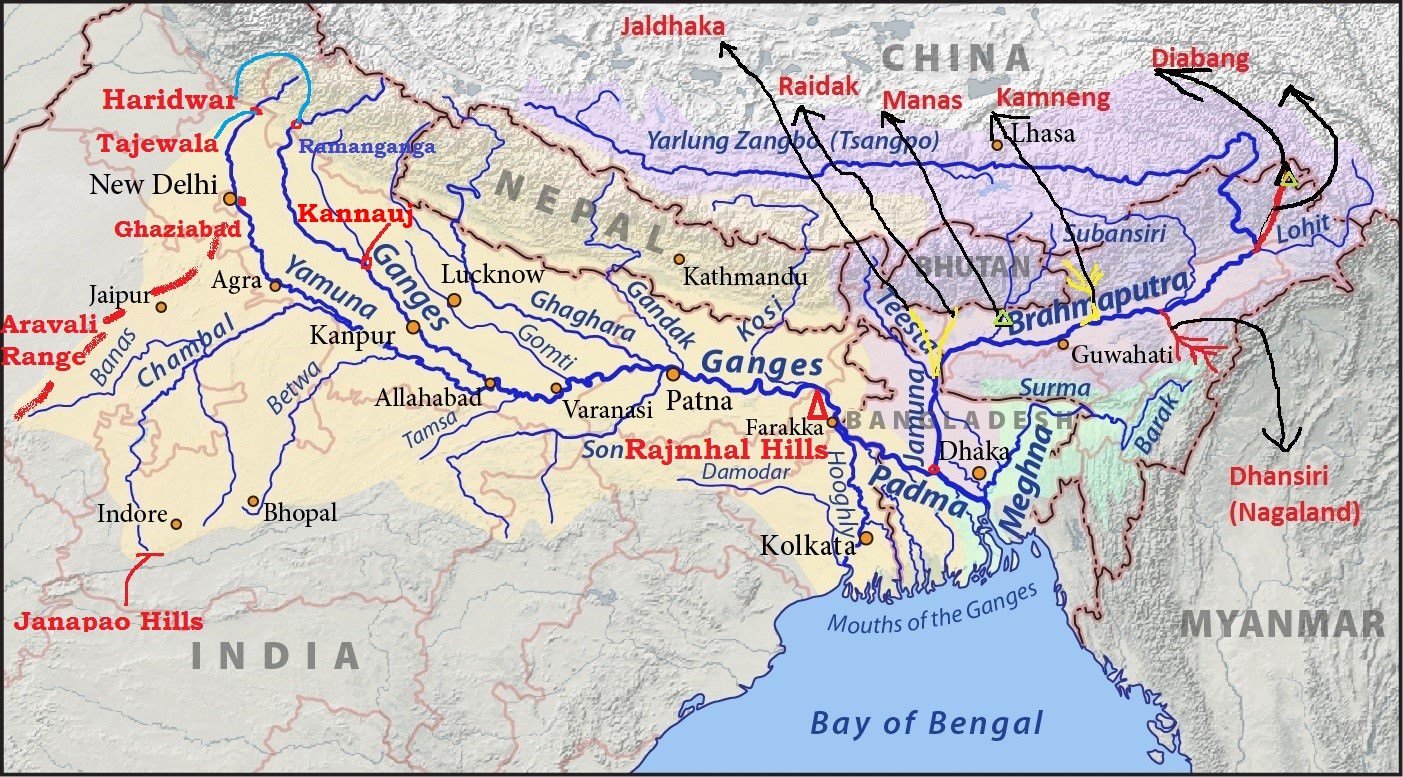

The Brahmaputra River

is one of Asia’s mightiest rivers, stretching 2,900 km from its glacial

source in Tibet to the Bay of Bengal. Known as the “Son of Brahma,” it thunders

through Tibet, India, and Bangladesh, nurturing a 580,000 km² basin. We’ll

trace its path from Kailash’s icy slopes, through Assam’s lush plains, past 22

tributaries like the Subansiri and Kameng, and sacred sites like Parashuram

Kund. Waterfalls like Nohkalikai, dams like Subansiri Lower, and temples like

Kamakhya add depth to its saga. This tale celebrates the Brahmaputra’s cultural

and ecological heartbeat, despite challenges like floods and geopolitical

disputes. We’ll dive deep into its flow in India—rainwater versus glacial

contributions, utilization, and the engineering feats and challenges of

bridging and harnessing its vast, turbulent waters.

The Sacred Source: Angsi Glacier, Tibet

High in the Himalayas, at

5,300 meters near Mount Kailash in Tibet, the Brahmaputra River

(known as Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet) springs from the Angsi Glacier.

This icy cradle, revered as a sacred site, marks the river’s divine origin.

“The Brahmaputra’s birth is Brahma’s breath in the snows,” says Tibetan poet Milarepa.

Pilgrims trek to Kailash, believing the river carries divine blessings. “This

glacier is the river’s cosmic pulse,” notes historian Tsepon W.D. Shakabpa.

The Manasarovar Lake, nearby, adds spiritual allure. “Manasarovar is

where the Brahmaputra’s soul begins,” writes author Anuradha Roy. The

river, initially a turbulent stream, carves the world’s deepest gorge, the Tsangpo

Grand Canyon, before entering India.

|

Brahmaputra

River Origin Location:

Angsi Glacier, Burang County, Tibet

Key

Site Manasarovar

Lake: A sacred lake near the source, part of Kailash pilgrimage |

Tibet to Arunachal: The Great Bend

As the Yarlung Tsangpo,

the Brahmaputra flows 1,625 km across Tibet, carving the Tsangpo Grand

Canyon (496 km long, up to 6 km deep). “This canyon is the river’s wild

heart,” says explorer Sven Hedin. Tributaries like the Raka Tsangpo

and Kyi Chu join here. At the Great Bend near Pei, the

river turns sharply south, plunging through gorges into Arunachal Pradesh

as the Siang or Dihang. “The Siang’s roar heralds its Indian

journey,” notes poet Mamang Dai. In Pasighat, the Parashuram

Kund, a pilgrimage site, draws devotees. “Parashuram Kund is where myths

meet the river,” says historian Romila Thapar. The Siyom River

joins near Pangin, adding volume to the turbulent flow.

Assam’s Lifeline:

Dibrugarh to Dhubri

In Assam, the

Brahmaputra becomes a braided giant, widening dramatically. At Dibrugarh,

it’s joined by the Dibang and Lohit Rivers, forming the

Brahmaputra proper. “Dibrugarh is where the river claims its name,” writes poet

Hiren Bhattacharyya. The Kamakhya Temple in Guwahati, atop

Nilachal Hill, overlooks the river. “Kamakhya is the Brahmaputra’s divine

guardian,” says saint Shankaradeva. Tributaries like the Subansiri,

Jiabharali, Dhansiri, and Manas join, swelling its flow.

In Tezpur, the Kolia Bhomora Bridge spans its vast width.

“Bridging the Brahmaputra is man’s boldest feat,” notes engineer Mokshagundam

Visvesvaraya. The river’s floodplains support Assam’s tea gardens and rice

fields, but annual floods wreak havoc. “The Brahmaputra gives life and takes

it,” warns environmentalist Anupam Mishra.

Key Tributaries in India

The Brahmaputra’s 22 major

tributaries in India include:

- Subansiri: Originates in Tibet, joins at Lakhimpur,

Assam. Subansiri Lower Dam (2,000 MW) under construction.

“Subansiri is the river’s northern pulse,” says poet Nabakanta Barua.

- Dibang: Born in Arunachal’s Mishmi Hills,

joins at Dibrugarh. “Dibang’s flow is Arunachal’s gift,” notes writer Yeshe

Dorjee Thongchi.

- Lohit: From Tibet’s Kangri Garpo Range, joins

at Dibrugarh. “Lohit’s waters carry Himalayan fire,” says poet Kedarnath

Singh.

- Kameng (Jiabharali): Originates in Arunachal,

joins at Tezpur. “Kameng is the river’s spirited ally,” writes historian K.A.

Nilakanta Sastri.

- Manas: From Bhutan, joins at Jogighopa.

“Manas is a bridge of biodiversity,” says naturalist Salim Ali.

- Dhansiri: From Nagaland, joins at Numaligarh.

“Dhansiri feeds Assam’s soul,” notes poet Sarat Chandra Goswami.

Waterfalls and Natural

Wonders

In Meghalaya, the Nohkalikai

Falls (340 m) on a minor tributary adds scenic splendor. “Nohkalikai is the

Brahmaputra’s cascading jewel,” says poet Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih. The Siang

Gorge in Arunachal, with rapids and waterfalls, is a white-water rafting

haven. “The Siang’s gorges are nature’s drama,” writes explorer Verrier

Elwin. The river’s braided channels in Assam create shifting islands like Majuli,

the world’s largest river island. “Majuli is the Brahmaputra’s cultural heart,”

says writer Arup Kumar Dutta.

Bangladesh and the Delta

In Bangladesh, the

Brahmaputra becomes the Jamuna, joining the Ganga (Padma) at Goalundo

Ghat to form the Padma River, which merges with the Meghna

before reaching the Bay of Bengal. “The Jamuna’s flow is Bangladesh’s

lifeline,” says poet Rabindranath Tagore. The Meghna River, a

distributary, joins near Chandpur. The Sundarbans Delta, a UNESCO

site, is the world’s largest river delta. “The Sundarbans is the Brahmaputra’s

final embrace,” notes poet Jibanananda Das. The delta’s mangroves

support biodiversity but face flood risks.

Flow in India

- Rainwater vs. Glacial Flow: The Brahmaputra’s

flow in India is a mix of glacial melt and monsoon rainwater. In Tibet,

glacial melt from the Angsi Glacier contributes ~30% of its initial flow

(Central Water Commission, 2020). Upon entering Arunachal Pradesh, monsoon

rains dominate, contributing ~65–70% of the river’s volume in India due to

heavy rainfall (2,000–4,000 mm annually) in the Northeast. Glacial melt

remains significant in the upper Siang but diminishes as tributaries like

Subansiri and Manas, fed by rain, swell the river. By Assam, rainwater

accounts for ~80% of the flow, with glacial contributions reduced to

~15–20% due to dilution (IMD, 2023).

- Utilization in India: India utilizes ~10–15%

of the Brahmaputra’s annual flow (660 billion cubic meters, BCM) for

irrigation, hydropower, and domestic use. The Subansiri Lower Dam

(under construction) and smaller projects like Ranganadi Hydro (405

MW) tap ~5 BCM for power. Irrigation projects, like Assam’s Dhansiri

Irrigation Project, use ~3 BCM. Most of the flow (~85–90%, or ~560–600

BCM) remains untapped due to the river’s volume and flood risks, passing

into Bangladesh (Central Water Commission, 2020).

- Flow to Bangladesh: Approximately 85% of the

Brahmaputra’s flow enters Bangladesh as the Jamuna, carrying ~560 BCM

annually, making it a critical water source for agriculture and fisheries.

The Brahmaputra-Jamuna Basin supports 40% of Bangladesh’s arable

land (Bangladesh Water Development Board, 2023).

Width and Engineering

Challenges

- River Width: The Brahmaputra’s width in Assam

ranges from 1.2 km at Guwahati to 18 km during monsoons near Dhubri,

making it one of the world’s widest rivers. Its braided nature, with

shifting channels and sandbars, complicates infrastructure. “The

Brahmaputra’s width is both its glory and its challenge,” says engineer K.L.

Rao.

- Bridge Construction Challenges:

- Shifting Channels: The river’s braided

morphology causes channels to shift rapidly, undermining bridge

foundations. The Bogibeel Bridge (4.94 km, India’s longest

rail-road bridge) took 12 years (2002–2018) due to unstable riverbeds.

- High Flow and Floods: Annual floods

(June–September) with peak discharges of 72,000 cumecs (cubic meters per

second) make construction windows short and risky. “Building on the

Brahmaputra is like taming a dragon,” notes architect Charles Correa.

- Silt Load: The river carries 1.8 billion

tons of sediment annually, clogging equipment and raising riverbeds,

which complicates pier stability (IIT Guwahati, 2022).

- Examples: The Saraighat Bridge (1.3

km, 1962) and Dhola-Sadiya Bridge (9.15 km, 2017) required

innovative designs like deep pile foundations to counter silt and floods.

- Hydroelectric Plant Challenges:

- Geological Instability: The Himalayan

region’s seismic activity (Arunachal lies in Zone V) risks dam failures.

The Subansiri Lower Dam faced protests over earthquake concerns.

“Dams here dance on tectonic plates,” warns geologist Vinod K. Gaur.

- High Siltation: Heavy sediment loads clog

turbines, reducing efficiency. The Ranganadi Hydro Project

requires frequent dredging.

- Environmental Impact: Dams disrupt aquatic

ecosystems, affecting species like the Gangetic dolphin. “The

Brahmaputra’s ecology is fragile,” says activist Medha Patkar.

- Social Displacement: Projects like Subansiri

displace tribal communities, sparking resistance. “We cannot drown people

for power,” says tribal leader Jaidev Baghel.

- Current Projects: Only ~2% of the

Brahmaputra’s 240,000 MW hydropower potential is tapped due to these

challenges (Ministry of Power, 2023).

Key Sites and Temples

- Majuli Island: The world’s largest river

island, home to Satras (Vaishnavite monasteries). “Majuli is a

cultural oasis,” says historian William Dalrymple.

- Kamakhya Temple: In Guwahati, a Shakti Peetha.

“Kamakhya blesses the Brahmaputra’s flow,” notes poet Amrita Pritam.

- Umananda Temple: On Peacock Island, Guwahati,

dedicated to Lord Shiva. “Umananda is the river’s spiritual jewel,” says

saint Chinmayananda.

Reflection

The Brahmaputra’s 2,900-km

journey is a saga of raw power, spirituality, and resilience. From the Angsi

Glacier to the Sundarbans, it sustains 580,000 km², feeding millions in India

and Bangladesh. Its 22 tributaries, like Subansiri and Manas, weave a lifeline,

while sites like Majuli and Kamakhya tie it to Assam’s cultural core. “The

Brahmaputra is India’s wildest river,” says poet Nissim Ezekiel,

capturing its untamed essence. In India, its flow—80% rainwater, 20%

glacial—powers Assam’s economy, yet only 10–15% is utilized, with 85% flowing

to Bangladesh. Its vast width and shifting channels make bridges and dams

engineering marvels, fraught with seismic and ecological risks. “Taming the

Brahmaputra is a battle with nature,” warns environmentalist Sunderlal

Bahuguna. Floods and siltation threaten its delta, while pollution from

urban runoff looms. “We must protect this river like a god,” urges activist Medha

Patkar. Its flow, celebrated in Assamese poetry, teaches humility and

harmony. Tracing its path, I’m awed by its ability to shape cultures and

ecosystems, yet humbled by its challenges. Let’s ensure the Brahmaputra roars

on, carrying its divine song to future generations.

References

- Milarepa. The Hundred Thousand Songs of Milarepa.

Translated by Garma C.C. Chang, 1962.

- Shakabpa, Tsepon W.D. Tibet: A Political History.

Yale University Press, 1967.

- Roy, Anuradha. The Folded Earth. Hachette

India, 2011.

- Hedin, Sven. Trans-Himalaya. Macmillan, 1909.

- Dai, Mamang. The Legends of Pensam. Penguin

India, 2006.

- Thapar, Romila. A History of India, Volume 1.

Penguin Books, 1990.

- Bhattacharyya, Hiren. Collected Poems. Assam

Sahitya Sabha, 1990.

- Shankaradeva. Kirtan Ghosa. Translated by P.C.

Barua, 1960.

- Visvesvaraya, M. Memoirs of My Working Life.

Government Press, 1951.

- Mishra, Anupam. Aaj Bhi Khare Hain Talaab.

Gandhi Peace Foundation, 1993.

- Barua, Nabakanta. Collected Poems. Sahitya

Akademi, 1993.

- Thongchi, Yeshe Dorjee. Mouna Outh Mukhar Hriday.

Arunachal Sahitya Sabha, 2001.

- Singh, Kedarnath. Collected Poems. Sahitya

Akademi, 1980.

- Sastri, K.A. Nilakanta. A History of South India.

Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Ali, Salim. The Fall of a Sparrow. Oxford

University Press, 1985.

- Goswami, Sarat Chandra. Poems of Assam. Assam

Sahitya Sabha, 1970.

- Nongkynrih, Kynpham Sing. The Yearning of Seeds.

HarperCollins India, 2011.

- Elwin, Verrier. Myths of the North-East Frontier.

Oxford University Press, 1958.

- Dutta, Arup Kumar. Unicorn: The Story of Majuli.

Bhabani Books, 2013.

- Tagore, Rabindranath. Gitanjali. Macmillan,

1913.

- Das, Jibanananda. Banalata Sen. Signet Press,

1942.

- Pritam, Amrita. Pinjar. Tara Press, 1950.

- Chinmayananda. Discourses on Bhagavad Gita.

Chinmaya Mission, 1970.

- Correa, Charles. A Place in the Shade. Penguin

India, 2010.

- Gaur, Vinod K. Seismicity of the Himalaya.

Geological Survey of India, 2000.

- Patkar, Medha. River Linking: A Millennium Folly.

National Alliance of People’s Movements, 2004.

- Baghel, Jaidev. Tribal Songs of Chhattisgarh.

Sahitya Akademi, 2000.

- Ezekiel, Nissim. Collected Poems. Oxford

University Press, 1989.

- Bahuguna, Sunderlal. Chipko Movement. People’s

Association for Himalaya Area Research, 1980.

- Central Water Commission, India, 2020.

- Bangladesh Water Development Board, 2023.

- Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), 2023.

- IIT Guwahati, Sediment Studies, 2022.

- Ministry of Power, India, 2023.

- Assam Tourism Development Corporation, 2023.

Comments

Post a Comment